SUMMARY

The author of the book Institutional Matrices and Development in Russia, Svetlana G. Kirdina, is a representative of the new generation of the Novosibirsk sociological school, which is known in Russia by its traditions and constant search for novel approaches. The work is one of the first Russian studies conducted within the framework of institutional sociology.

In 2000, the book was awarded the 3rd prize in a scientific monographs’ competition organized by the Russian Sociology of Sociologists. The Russian Foundation for Fundamental Research supported the publication of this book. It generalizes and finesses the theses of the institutional matrices macrosociological theory, which has been elaborated by the author since mid-1990s. The author argues that the institutional structure of societies is characterized by either an X- or Y-matrix, which determines various ways of evolutions of the corresponding states. To prove this statement, the author provides rich empirical evidence from economic, political and ideological practices of both ancient and modern states of Europe, America, Asia, but, primarily, Russia.

The book opens with a Preface to the first edition outlining problems to solve which new theoretical schemes of sociological research need to be constructed. Why, for instance, revolutions that Karl Marx had predicted took place not in the West, as was his suggestion, but in Russia, Latin America, and South-Eastern Asia? Why, despite the globalization of world development, it is not necessarily true that an economic or social form borrowed by a state from another state’s experience would be successfully implemented and not turn into its opposite? Why reform processes are so diverse in post-Soviet space; why things easily implemented in East European countries do not work in Russia? What determines the type of society and the direction of its historic evolution; where are limits to institutional change?

Classical sociological theories do not provide us with a satisfactory answer to these and other questions. Social practice defies the academics and demands new theoretical hypotheses, new concepts and categories, that would be able to embrace and explain the ongoing social processes.

Therefore, there has appeared a need to study the nature of societies more thoroughly, to find out its basic, “matrix” structures that latently determine the variety and direction of the processes taking place “on the surface” of social life. The institutional matrices theory suggested and developed by the author is designed for this very purpose.

The Preface to the second edition states additional and revision moments that make the book different from the first edition.

The Introduction dwells on requirements to sociological theories, as well as provides an analysis of the Russian situation that stimulates a construction of new methodological conceptions. The author turns to a number of studies to show that traditional theories cannot account for the behavior of monumental institutions which seem evident for the West and, in the Russian context, become diverse and unpredictable.

Part I centers on the main concepts and first illustrations to the institutional matrices theory taking examples from the history of ancient states.

Chapter 1 sets forth the main postulates suggested by the author. First, the theory is developed within the objectivist paradigm which follows the sociological tradition of E. Durkheim, K. Marx, and T. Parsons. This approach regards society as a social system which exists objectively and develops according to its own laws, independent of will and actions of particular individuals. Second, an analysis of tendencies in the study of institutions is suggested, and the notion of basic institutions is introduced, the latter being in-depth, historically stable social relations which constantly reproduce themselves and provide the integrity of different types of societies. Basic institutions are historic invariants that let a society survive and develop, while preserving its self-sufficiency and integrity in the course of historic evolution. Basic institutions differ from institutional forms in which they are incarnated at different stages of historic development, depending on civilization and cultural context. Institutional forms are mobile, flexible, changeable, whereas basic institutions are stable, permanent, immutable. Third, a society is seen as a social system, the main datum lines within “sociological co-ordinates” being economy, politics and ideology. Each sphere is regulated by a corresponding set of basic institutions.

Chapter 2 examines the notion of an institutional matrix, singles out its types and analyses its features.

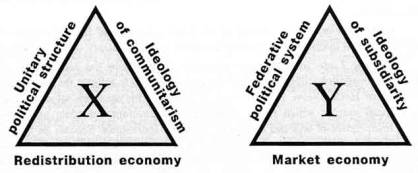

An institutional matrix (a derivative from the Latin “queen; foundation; primary model”) is a system of basic institutions which unite economy, politics and ideology, and regulate the functioning of a state as a whole (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Institutional matrix' scheme

An institutional matrix is at the core of the changing empirical states of particular societies, it assures that their institutional nature is preserved and reproduced.

Two ideal types of institutional matrices that differ qualitatively and aggregate a whole variety of states of a society as a social system can be singled out: an X-matrix and an Y-matrix. They differ in a set of basic institutions forming them (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. The difference between two types of institutional matrices

An X-matrix is characterized by the following basic institutions:

- in the economic sphere: redistribution economy institutions (term coined by K. Polanyi’s). Redistribution economies are characterized by a situation when the Center regulates the movement of goods and services, as well as the rights for their production and use;

- in the political sphere: institutions of unitary (unitary-centralized) political order;

- in the ideological sphere: institutions of communitarian ideology, the essence of which is expressed by the idea of dominance of collective, public values over individual ones, a priority of We over I.

An X-matrix is characteristic of Russia, most Asian and Latin American countries and some other.

he following basic institutions belong to an Y-matrix:

- in the economic sphere: institutions of market economy;

- in the political sphere: institutions of federative (federative-subsidiary) political order;

- in the ideological sphere: institutions of the ideology of subsidiarity which proclaims the dominance of individual values over values of larger communities, the latter bearing a subsidiary, subordinating character to the personality, i.e. a priority of I over We.

An Y-matrix is characteristic of the public order of most countries of Western Europe and the USA.

Main features of institutional matrices are discussed in this chapter. Symmetry and invariance are among them. The notion of a complementary institution is introduced denoting an institution generated within one institutional matrix and using its characteristic institutional forms in the context of basic institutions of the alternative institutional matrix. The principle of the dominance of basic institutions over complementary ones is given prove to. In other words, in each particular society, basic institutions characteristic of its institutional matrix dominate over complementary institutions. The latter serve as auxiliary, additional, providing stability of the institutional environment in a particular sphere of society. Just as a dominant gene in genetics, that dominates over a recessive gene and, thus, determines the features of a living organism, so basic institutions set the framework and limitations for the action of complementary, auxiliary institutions. It is argued that the action of basic institutions and corresponding institutional forms is rather spontaneous, unregulated, whereas the development of complementary institutions and forms which, in accordance with basic institutions, assure a balanced development of a particular public sphere, requires purposeful efforts on behalf of social agents. In the absence of such efforts, the elemental, spontaneous action of basic institutions may bring chaos and crisis to the society.

Chapter 3 explains the role of material-technological environment for the formation of a particular type of institutional matrix. The author distinguishes between a communal environment and a non-communal one. Communality denotes such a feature of the material-technological environment which assumes that it is used as a unified, further indivisible system, parts of which cannot be taken out without a threat of its disintegration. A communal environment can function only in the form of a public good which cannot be divided into consumption units and sold (consumed) by parts. Accordingly, joint, coordinated efforts on behalf of a considerable part of the population, and a unified centralized government are needed. Therefore, the institutions’ contents of a state which is developing within a communal environment is, eventually, determined by the tasks of coordination of joint efforts towards its effective usage. Thus, an X-matrix is formed under communal conditions. Whereas non-communality signifies a technological dissociation, a possibility of atomization of the core elements of material infrastructure, as well as a related possibility of their independent functioning and private use. Non-communal environment is divisible into separate, disconnected elements, it is able of dispersion and can exist as an aggregate of dissociated, independent technological objects. In this case, an individual or a family can involve parts of non-communal environment in their economy, maintain their effectivity, and use the obtained results on their own, without cooperating with other members of the society. If this is the case, the main function of the thus-forming social institutions is to assure an interaction between the atomized economic and social agents. An Y-matrix is shaped in a non-communal environment.

With illustrations from the history of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, Chapter 4 shows that, from the beginning of human history, states have appeared and co-existed that differed in their type of institutional matrices. An X-matrix is characteristic of Egypt, whereas an Y-matrix is characteristic of Mesopotamia.

Part II (Chapters 5-7) presents a detailed analysis of sets of basic institutions characteristic of X- and Y-matrices.

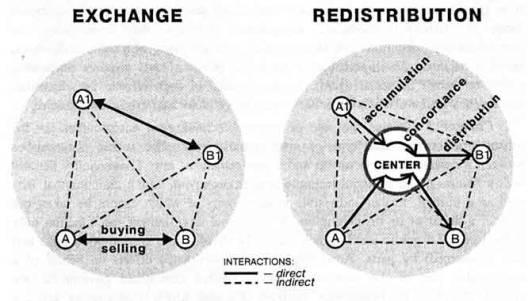

Chapter 5 presents an analysis of institutions of market and redistribution economies. Market economy institutions have been studied rather thoroughly, starting with work by Adam Smith, whereas redistribution economies may be said to have been studied relatively poorly. The book examines and comments on ideas of Karl Polanyi who approached these economies from the institutional standpoint. Although, at the “surface” of social life, relations between economic agents in various types of societies seem alike, quite different institutional mechanisms underlie them (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Interactions between the economic agents in the redistribution and exchange models

In the market economy, most important is the process of lateral interaction in the form of buying and selling; it is shown by a bold arrow connecting agent A with agent B in the exchange model. Dotted arrows signify mediated connections of the agents under consideration with other members of the market. These connections mean that terms of transactions between certain agents are defined by a shaping market situation, i.e. the level of prices, costs, presence of similar and alternative goods, etc.

In redistribution economies, the process of interaction between agent A and agent B is a result of the process of coordination which takes place at the level of the Center and is determined by the process of accumulation and distribution of goods and services. Therefore, these processes are drawn with bold arrows which underline the primacy of relations of redistribution; whereas direct contacts between economic agents in this context are marked with dotted arrows which are designed to draw attention to their secondary, dependent character.

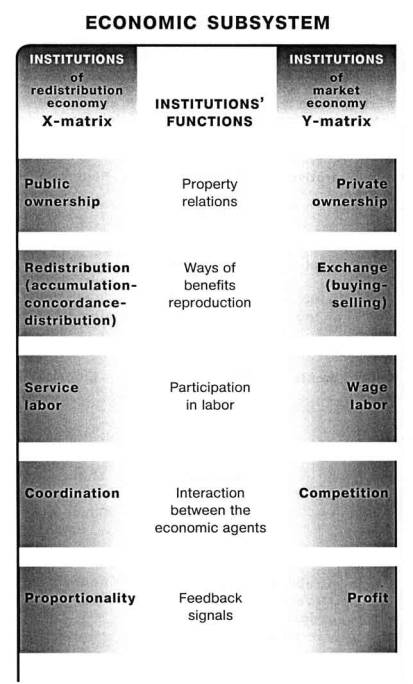

The differences between basic institutions regulating market and redistribution economies are shown in Scheme 4.

Scheme 4. Basic institutions of redistribution and market economies

It can be seen that in different types of economies, different basic institutions appear to perform the same functions.

The last section of the chapter is devoted to an analysis of the interaction between basic and complementary economic institutions, illustrated by examples drawn from the history and current practice of different countries.

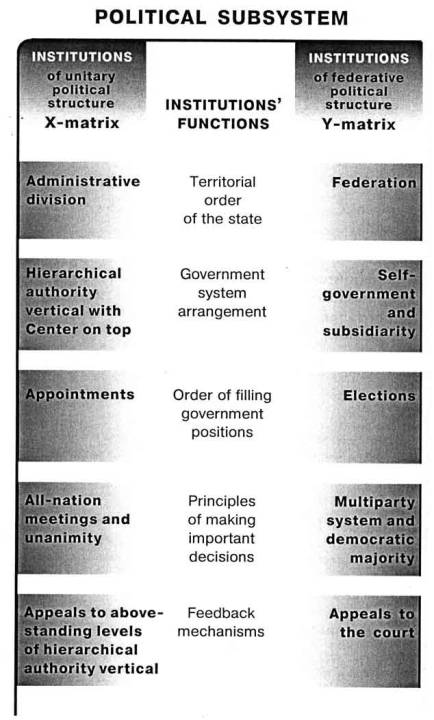

Chapter 6 dwells on institutional sets characteristic of the unitary and federative political order (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. Basic institutions of unitary and federative political structure

An analysis is suggested of examples of the interaction between basic and complementary political institutions in different countries, instances of metamorphoses that happen to borrowed political forms within alternative institutional matrices are provided.

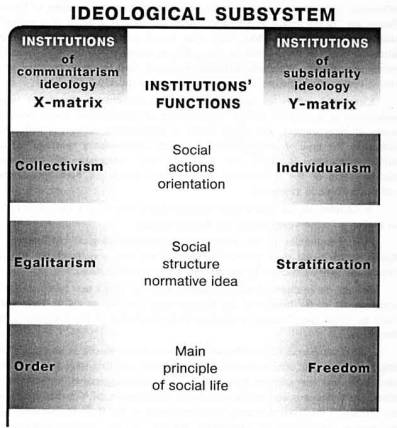

In Chapter 7, basic institutions are analyzed that shape the complex of the ideology of communitarism and the ideology of subsidiarity characteristic of the states with X- and Y-matrices (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6. Basic institutions of communitarism and subsidiarity ideologies

Besides a description of these various “pure” institutional complexes, peculiarities of the interaction between basic and complementary ideological institutions in some countries at certain stages of their development are considered.

Part III (Chapters 8-10) studies both stability of institutional matrices, and institutional change. Special attention is paid to the analysis of processes of transformation of the Russian society on the basis of the institutional matrices theory, as well as to a forecast of the course and results of Russian reforms.

Chapter 8 elaborates on and provides empirical evidence to the idea of the invariance and stability (sustainability) of institutional matrices. Different from the wide-spread notions on the nature of revolutions, an argument is suggested that a revolution is a moment in an evolutionary process, it is a spontaneous recurrence of social structures to the initial institutional matrix, which had been deformed as a result of unconscious actions of social agents either within a state, or under outside influences. For instance, the modern so-called revolutions in the states of Eastern Europe are “restitutional” by character. After the war, as a result of a powerful outer influence from the USSR, they were forced to develop institutions of the alternative social system, which, in most of these countries, contradicted the initial institutional matrix. When this influence weakened, East-European countries were able to restitute their historic institutional order rather quickly.

Chapter 9 offers an analysis of institutional change, the latter being understood as a process of the improvement of institutional forms both by means of inner sources, and in the course of institutional exchanges with other countries. The type of institutional matrix only determines a “passage” of the social evolution, it does not eliminate the processes of permanent modernization of the institutional environment, which are both spontaneous and controllable in character.

In Chapter 10, the institutional matrices theory is used as a methodology for an analysis of the development of the Russian society. First, peculiarities of the communal material-technological environment in Russia, which made their presence already in the first periods of the Russian history and have augmented by the present, are described in detail. Second, the institutional matrices theory allows to give a new interpretation to some periods of the history of the Russian state – to the so called Tatar yoke, Peter the Great rule, Russian revolutions of the beginning of the XX century, the Soviet era. Third, the course of transformation of post-Soviet Russia is analyzed. Two stages of the current reforms have been singled out. The first stage (late 1980-s – late 1990s) was characterized by an active, sometimes aggressive, introduction of alternative institutions and institutional forms characteristic of Y-matrix states into the practice of the Russian society. The termination of this stage is associated with an explicit appearance of communal features of the material-technological environment – conditions, under which the dominance of market institutions, federative principles of political order, and subsidiary ideology become ineffective. The second stage is characterized by a more rigid appointment of niches for complementary institutions and a shift to the improvement of institutional forms characteristic of the X-matrix of the Russian society.

In the Conclusion, possibilities of institutional matrices theory as applied to the explanation of some arguable points of the institutional theory, as well and as a perspective of its further development are presented.

A “Tree” of Institutional Matrices Theory Terms, a Glossary, and a Bibliography containing about 300 items are attached.

The author would be grateful for any comments on the book.

Please email: Этот e-mail адрес защищен от спам-ботов, для его просмотра у Вас должен быть включен Javascript